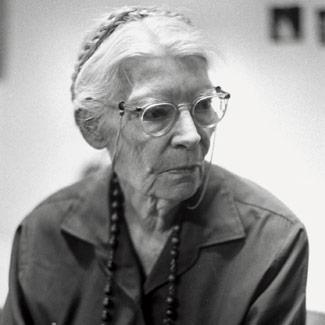

Dorothy Day (Journalist/Social Activist)

Dorothy Day (November 8, 1897 – November 29, 1980) was an American journalist, social activist, and devout Catholic convert; she advocated the Catholic economic theory of Distributism.

Dorothy Day (November 8, 1897 – November 29, 1980) was an American journalist, social activist, and devout Catholic convert; she advocated the Catholic economic theory of Distributism.

She was also considered to be an Anarchist, and did not hesitate to use the term.

A revered figure within the U.S. Catholic community, Day's cause for canonization is open in the Catholic Church.

In the 1930s, Day worked closely with fellow activist Peter Maurin to establish the Catholic Worker movement, a nonviolent, pacifist movement that continues to combine direct aid for the poor and homeless with nonviolent direct action on their behalf.

Dorothy Day was born in Brooklyn, New York, and raised in San Francisco and Chicago. She was born into a family described by one biographer as "solid, patriotic, and middle class".

Her father was a Southerner of Scotch-Irish background, while her mother, a native of upstate New York, was of English ancestry. Her parents were married in an Episcopal church located in Greenwich Village, a neighborhood where Day would spend much of her young adulthood.

In 1914, Dorothy Day attended the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign on a scholarship, but dropped out after two years and moved to New York City. Day was a reluctant scholar. Her reading was chiefly in a radical social direction. She avoided campus social life and insisted on supporting herself rather than live on money from her father, a characteristic she was to maintain for the rest of her life, to the point of buying all her clothing and shoes from discount stores to save money.

Settling on the Lower East Side, she worked on the staffs of Socialist publications (The Liberator, The Masses, The Call) and engaged in anti-war and women's suffrage protests. She spent several months in Greenwich Village, where she became close to Eugene O'Neill.

Initially Day lived a bohemian life, with two common-law marriages and at least one abortion, which she later described in her semi-autobiographical novel, The Eleventh Virgin (1924)—a book she later regretted writing. She had been an agnostic, but with the birth of her daughter, Tamar (1926–2008), she began a period of spiritual awakening which led her to embrace Catholicism, joining the Church in December 1927, with baptism at Our Lady Help of Christians parish on Staten Island. In her 1952 biography, The Long Loneliness, Day recalled that immediately after her baptism, she made her first confession, and the following day, she received communion. Subsequently, Day began writing for Catholic publications, such as Commonweal and America.

The Catholic Worker movement started with the Catholic Worker newspaper, created to promote Catholic social teaching and stake out a neutral, pacifist position in the war-torn 1930s. (See The Catholic Worker: The Aims and Means of the Catholic Worker.) This grew into a "house of hospitality" in the slums of New York City and then a series of farms for people to live together communally. She lived for a time at the now demolished Spanish Camp community in the Annadale section of Staten Island. The movement quickly spread to other cities in the United States, and to Canada and the United Kingdom; more than 30 independent but affiliated CW communities had been founded by 1941. Well over 100 communities exist today, including several in Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, the Republic of Ireland, Mexico, New Zealand, and Sweden. She was also a member of the Industrial Workers of the World ('Wobblies').

By the 1960s, Day was embraced by a significant number of Catholics, while at the same time, she earned the praise of counterculture leaders such as Abbie Hoffman, who characterized her as the first hippie, a description of which Day approved. Yet, although Day had written passionately about women’s rights, free love and birth control in the 1910s, she opposed the sexual revolution of the 1960s, saying she had seen the ill-effects of a similar sexual revolution in the 1920s. Day had a progressive attitude toward social and economic rights, alloyed with a very orthodox and traditional sense of Catholic morality and piety.

Her devotion to her church was neither conventional nor unquestioning, however. She alienated many U.S. Catholics (including some clerical leaders) with her condemnation of Falangist leader Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War; and, possibly in response to her criticism of Cardinal Francis Spellman, she was pressured by the Archdiocese of New York in 1951 to change the name of her newspaper, "ostensibly because the word Catholic implies an official church connection when such was not the case".

In 1971, Day was awarded the Pacem in Terris Award. It was named after a 1963 encyclical letter by Pope John XXIII that calls upon all people of good will to secure peace among all nations. Pacem in Terris is Latin for 'Peace on Earth.' Day was accorded many other honors in her last decade, including the Laetare Medal from the University of Notre Dame, in 1972.

She died on November 29, 1980, in New York City.

Day was buried in Cemetery of the Resurrection on Staten Island, just a few blocks from the location of the beachside cottage where she first became interested in Catholicism. She was proposed for sainthood by the Claretian Missionaries in 1983. Pope John Paul II granted the Archdiocese of New York permission to open Day's "cause" for sainthood in March 2000, thereby officially making her a "Servant of God" in the eyes of the Catholic Church.